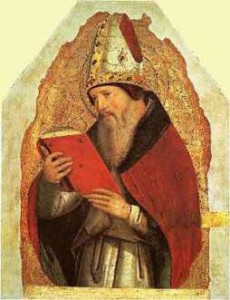

Pavia: Saint Augustine

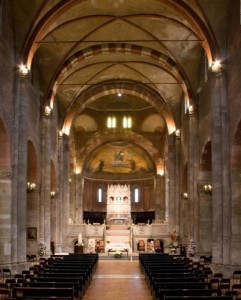

Basilica di San Pietro in Ciel d’Oro (Piazza S. Pietro in Ciel d’Oro; 7.15am-12 / 3-7pm; santagostinopavia.wordpress.com)

Pavia, the last repose of St. Augustine of Hippo, can easily be reached from Milan. I’ve managed to comfortably fit both Pavia and Bosco Marengo (the birth place of St. Pius V) into a day trip, returning to Milan in the evening.

(In case someone else sets out to do this without a car, here’s how… The short 30 minute journey on a regional train from Milan’s Central station to Pavia allowed me to spend several hours at St. Augustine’s church and explore the centre of Pavia. At noon I hopped on another train taking me, in a total of 1h 40min, from Pavia via Alessandria to Frugarolo-Bosco Marengo. The trip back, from Frugarolo-BM, again via Alessandria, to Milano Centrale lasted in total about two hours.)

Speaking of St. Pius V, Pavia is also home of the Ghislieri College he had founded. See information and photos at the very end of this post.

But now back to St. Augustine…

The first mention of the basilica San Pietro in Ciel d’Oro (St. Peter in the Golden Sky) dates back to the year 602, though the present Romanesque church is from the 12th century. It is the resting place of St. Augustine, whose relics are deposited in a silver urn at the foot of the marble Ark. The Ark, a masterpiece by 14th century Lombard sculptors, is carved with scenes from the saint’s life.

In the sacristy there is a little shop with many interesting items related to the bishop of Hippo.

SAINT AUGUSTINE, BISHOP OF HIPPO, DOCTOR OF GRACE, PILLAR OF CHRISTENDOM

“A philosophical and theological genius of the first order, dominating, like a pyramid, antiquity and the succeeding ages. Compared with the great philosophers of past centuries and modern times, he is the equal of them all; among theologians he is undeniably the first, and such has been his influence that none of the Fathers, Scholastics, or Reformers has surpassed it.” Thus describes Philip Schaff, Church historian and Protestant, St. Augustine of Hippo.

More than just a theological giant towering above the other Church Fathers, St. Augustine was a fearless and uncompromising defender of the Faith against heresies, a tireless pastor of his flock, and a perfect model of a true penitent; an inspiration to Christians throughout the ages.

Augustine’s life: From sinner to saint

Augustine was born on November 13, AD 354 in Thagaste, in the Roman province of Africa (present-day Algeria) to an aristocratic, though not very wealthy, family. His mother St. Monica was a devout Christian; it was thanks to her virtues, prayers and holiness that her pagan husband and Augustine’s father Patricius finally converted, on his death bed, to Christianity.

Reading Cicero and other philosophers left a deep impact on young Augustine, fomenting his interest in philosophy and a love of wisdom. At 17 he went to Carthage to study rhetoric and, lauded for his powerful intellect even at such early age, soon became filled with vanity, ambition and pride.

A brilliant mind blinded by sin

Despite his brilliant mind and Christian upbringing, Augustine, ceding to the seductions of the half-pagan city and the licentiousness of his fellow students, embraced a life of hedonism, immorality, and false beliefs. For nearly 15 years he kept a concubine with whom he had a son, Adeodatus. Worldly ambitions, intellectual pride and a life of sin and impurity darkened Augustine’s mind, making him seek the truth in all the wrong places. So blinded became his understanding that he abandoned the faith of his mother and (by AD 373) enthusiastically embraced the dreadful Manichaean heresy. (Rather than a Christian heresy Manichaeism was actually a pagan religion, based on dualism, which borrowed elements from Christianity, Gnosticism, Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, etc.)

Augustine was restless in his search for the Truth. His pride – cause of his displeasure with the Sacred Scriptures, the humility and simplicity of which he found offensive to his intellect – was flattered by the Manichaeans who promised knowledge of nature and its laws, and answers to all the philosophical and spiritual questions, in particular to the “problem of evil” that Augustine had been troubled by.

The Manichaeans believed that the world was in perfect tension between two equal powers, a good and an evil one, an inevitable struggle between the spiritual world of light and the material world of darkness. Their doctrine, which ultimately denied liberty and attributed the commission of evil to an outside force, was convenient for Augustine who was living a life of lust and sin.

He would later admit in his Confessions: “I still thought that it is not we who sin but some other nature that sins within us. It flattered my pride to think that I incurred no guilt and, when I did wrong, not to confess it… I preferred to excuse myself and blame this unknown thing which was in me but was not part of me. The truth, of course, was that it was all my own self, and my own impiety had divided me against myself. My sin was all the more incurable because I did not think myself a sinner.”

Search for the Truth

For nine years Augustine taught rhetoric in Carthage, earning recognition and applause. In AD 383 he moved to Rome to open a school of rhetoric but, growing disgusted with students defrauding him on tuition fees, left for Milan the following year to become a professor of rhetoric at the imperial court. St. Monica joined her son in Milan and at last convinced him to abandon his concubine and to let her arrange a marriage for him. However, during the two years Augustine had to wait for his fiancée to come of age, he took another concubine. (Augustine famously prayed, “grant me chastity and continence, but not yet”.) He would later break off the engagement to embrace a life of Christian chastity.

Augustine started becoming disillusioned with Manichaeism even before he left Carthage, put off by the feebleness of the arguments in defense of their doctrine, lack of the knowledge they had promised him, as well as by his disappointing debate with the celebrated Manichaean bishop Faustus of Mileve. In Rome he turned away from the Manichaeans only to spend three more years in spiritual wandering, attracted to a number of philosophies (the skepticism of the New Academy movement, the Neo-Platonism of Plotinus, etc). At last, thanks to his mother’s constant prayers and the sermons of Milan’s holy bishop St. Ambrose, Augustine found the long-sought truth in Jesus Christ and His Church. Yet, unable to imagine living a pure life, he did not immediately convert to what he now recognized as the only true religion.

Augustine started becoming disillusioned with Manichaeism even before he left Carthage, put off by the feebleness of the arguments in defense of their doctrine, lack of the knowledge they had promised him, as well as by his disappointing debate with the celebrated Manichaean bishop Faustus of Mileve. In Rome he turned away from the Manichaeans only to spend three more years in spiritual wandering, attracted to a number of philosophies (the skepticism of the New Academy movement, the Neo-Platonism of Plotinus, etc). At last, thanks to his mother’s constant prayers and the sermons of Milan’s holy bishop St. Ambrose, Augustine found the long-sought truth in Jesus Christ and His Church. Yet, unable to imagine living a pure life, he did not immediately convert to what he now recognized as the only true religion.

Conversion

In AD 386, after hearing of a sudden conversion of certain men, Augustine, full of anguish, shame and anger at himself, cried out to a friend: “What are we doing? Unlearned people are taking Heaven by force, while we, with all our knowledge, are so cowardly that we keep rolling around in the mud of our sins!”

Storming out to the garden, he heard a child-like voice singing tolle, lege, tolle, lege (take and read, take and read). Opening his Bible Augustine read the first thing his sight fell on, and it applied perfectly to his disordered life. It was St. Paul’s Epistle to the Romans, chapter 13, verse 13-14: “Not in rioting and drunkenness, not in chambering and impurities, not in contention and envy. But put ye on the Lord Jesus Christ: and make not provision for the flesh in its concupiscences.” He didn’t need to read any further. It was at that very moment Augustine determined to put away all impurity – which was, as he now recognized, what had kept him away from the Truth all those years – and live his life in imitation of Christ.

Shortly thereafter he resigned his professorship and went with Monica, Adeodatus and a few friends to the country estate Cassisiacum to study Christian doctrine and philosophy. (Augustine continued to be influenced by neo-Platonism so long as it agreed with Christian doctrine; wherever it contradicted, he subordinated philosophy to religion, reason to faith.) At Cassisiacum he wrote his Dialogues, revealing the details of his conversion, the arguments that convinced him (particularly the life and conquests of the Apostles), his progress in the Faith at the school of St. Paul, the delightful conferences with his friends on the Divinity of Jesus Christ, the wonderful transformations worked in his soul by grace, his victory over intellectual pride and the calming of his passions.

To the great joy of his mother and his friend (priest and later bishop of Milan) Simplicianus, Augustine was baptized – along with his son Adeodatus – at Easter of AD 387, in Milan, by St. Ambrose. It was through the influence, preaching and example of this holy bishop and Doctor of the Church that the light of the Truth finally entered Augustine’s soul. He was 33 when he became a Catholic – the age of Jesus at His death and resurrection. [My own conversion also happened at the age of 33. Having not only equaled but far outdone Augustine in the life of sin, I pray to at some point reach a fraction of his virtues and holiness.]

Thus Ambrose’s promise to Augustine’s mother (who never stopped praying and sacrificing for her son’s conversion) – that “a son of so many tears could not perish” – became fulfilled. The following year Augustine wrote his first book, On the Holiness of the Catholic Church. Augustine, Monica and Adeodatus then left Milan to return to North Africa; it was during this journey that his mother Monica died, in Ostia (AD 388). She was followed not long after by Adeodatus. Augustine then sold his patrimony and distributed the money to the poor, keeping only his family villa where he and a group of friends withdrew to lead a life of poverty, prayer and the study of sacred texts.

Augustine, priest and bishop

In AD 391, yielding at last to the wishes of the people and of bishop Valerius, Augustine was ordained priest in Hippo. He became well known for his preaching and his combat of the Manichaean heresy. Four years later he was made bishop of Hippo, to remain in that position until his death. Bishop Augustine continued to lead an austere and penitential life, shunning all temptations of the world and the flesh. His episcopal residence became a quasi-monastery where the bishop lived a community life with his clergy who bound themselves to observe religious poverty. Ten of his disciples and friends became bishops; others founded monasteries that soon spread all over Africa. (St. Augustine’s monastic community and rule would later become the model for the Augustinian Order.)

More than anything else, St. Augustine was a firm defender of the Truth and a zealous pastor of souls. He preached up to five times a day on topics relating to Catholic doctrine and moral teachings, and their practical application to the lives of his flock, personal holiness, life of prayer, etc. His sermons, letters and books, as well as his presence at several councils defending Catholic doctrine against errors, have had an immense influence on the Church and on Catholic life. (Augustine also played a prominent role at the third Council of Carthage, AD 397, which affirmed the canon of Sacred Scripture.)

Defender of the Faith against the heretics

Using his untiring zeal, powerful intellect and brilliant oratory skills to defend the true Faith, St. Augustine became God’s instrument in fighting and overthrowing heresies – Manichaeism, Priscillianism, Donatism, Pelagianism and Arianism.

At the time he became a priest and bishop large numbers of the Christians in Africa were infected by the Donatist heresy. The Donatists were against the Church’s readmission of those who, during the Roman persecutions, denied or renounced their faith (traditores). They held that even after lengthy public penance such people could not be received back into the Church. Thus the Donatists refused sacraments and spiritual authority of clergy who had at some point apostatized under persecution, claiming that the validity of the sacraments depended on the moral character of those administering them. Perpetrating many outrages and violence, the Donatists murdered large numbers of Catholics; St. Augustine himself was the target of several of their assassination attempts.

Gradually, by the bishop’s zeal, learning and sanctity, as well as Emperor Honorius’ laws against the Donatists, the Catholics gained ground. In AD 411 the Donatist doctrine was shown to be false at the conference of Carthage. St. Augustine, in disputations between the assembled 286 Catholic and 279 Donatist bishops, proved the Donatists to be in error. He explained that the sacraments were valid and efficacious even when administered by an unworthy priest, for Christ was the actual actor of the sacrament. He further affirmed that mercy and forgiveness could be granted to all repentant sinners, even to the traditores. Augustine’s defense of Catholic doctrine was successful and vast numbers of Donatists, including many bishops with their whole flocks, came back into the Catholic Church. The Emperor ordered Donatist clergy to be banished from Africa and their churches restored to the Catholics.

The bishop of Hippo was equally firm in condemning the heresy of Pelagius and his followers. The Pelagians denied both original sin and the necessity of divine grace (as well as of the sacraments) for salvation. It was largely due to Augustine’s efforts that Pelagius and his chief disciple Celestius were condemned as heretics and excommunicated (AD 417).

His arguments against Pelagianism helped Augustine refine the doctrine of original sin and the doctrine of the necessity of God’s grace for man’s salvation. He clearly proved from passages in Holy Scriptures that all men were sinners and could gain no merit on their own but only through Christ. He further taught that virtues and good works (even if they were not infected by motives of self-love, vainglory or other passions) could never be meritorious of eternal life unless done for God alone; and such supernatural motive could only be produced by divine grace.

Death and translation of relics

In AD 428 the Vandals, adherents of the (already condemned) Arian heresy, invaded Roman Africa, leaving cities in ruins, burning churches, slaying the population and murdering bishops and priests. Two years later they besieged Hippo. Bishop Augustine, by then gravely ill and close to death, spent his last days in prayer and penance, while ordering the safeguarding of all the books he had bestowed on the church of Hippo. He died on August 28 of that same year (AD 430). Not long thereafter the Vandals sacked and burned down the city of Hippo. The only things they left untouched were Augustine’s cathedral, his remains and library.

The Catholic bishops later expelled by the Vandals from North Africa translated Augustine’s body to Cagliari in Sardinia. In AD 724 the saint’s remains were transferred – after being redeemed for their weight in gold from the Saracens – by the pious Lombard king Liutprand and his uncle, the bishop of Pavia, to the basilica San Pietro in Ciel d’Oro in Pavia. Liutprand had the sacred relics placed in several coffins engraved with the saint’s name and carefully hidden in the crypt, where they were rediscovered in 1695. In 1700 the Augustinians, expelled from Pavia by the Napoleonic armies, found refuge in Milan, taking Augustine’s remains with them. Two centuries later, after the Augustinians regained and restored their church San Pietro in Ciel d’Oro, the saint’s relics returned. This is where they remain to this day, resting in a silver urn at the foot of the magnificent marble Ark. (King Liutprand is also buried in the basilica.)

Saint Augustine was declared a Doctor of the Church by Pope Boniface VIII in 1298. His feast day is celebrated on August 28.

Nature, grace and free will

One of the fruits of St. Augustine’s long battle with the heretics is the profound explanation he has left us of various Catholic doctrines, particularly those of original sin, free will, nature and grace.

Against the Manichaeans the saint affirmed that God gives each man the grace necessary for his salvation, yet He does not take away man’s free will. Being all-powerful and all-knowing, God has always known how each soul would respond to this grace, but He nevertheless leaves man the liberty to choose. (God wants us to love Him and to be with Him in eternity, but it has to be of our free will; He will not force anyone to love Him, for a forced love would be no love at all.) As St. Augustine told the Manichaeans, “all can be saved if they wish”.

His explanations of nature and grace earned the bishop of Hippo the name of Doctor of Grace. Like St. Paul, the Apostle, St. Augustine taught that the grace of God is a gift, free and unmerited, and necessary for our salvation. This necessary grace is never wanting, but through our fault.

In AD 415 he wrote his famous book On Nature and Grace (De Natura et Gratia) against the Pelagian heresy. The Pelagians, denying original sin, taught that man can be saved without baptism or grace, that he doesn’t need God to be good but can rely on his own nature. (Due to the fallen human nature all men harbor pride in their heart, and hence have a tendency to Pelagianism, believing in their own strength, merit and self-sufficiency.)

St. Augustine demolished their errors and thoroughly demonstrated that man, by his own powers, could never earn or attain salvation and sanctity. No natural virtue can be meritorious of eternal life; only that which is animated by the supernatural, by divine charity produced by supernatural grace. Thus only by God’s grace can man do anything good (profitable for his salvation). All that is good in us must be attributed to Him. While God dispenses His grace freely, man can obstruct its flow by turning away from God, by sin.

Original sin

The Scriptures tell us that Adam and Eve were righteous in the Garden of Eden before they sinned. It was the sin of our first parents that brought death and misery into the world. Augustine affirmed, against the Pelagians, that Adam and Eve possessed – before they sinned – the gratuitous gifts of immortality, freedom from suffering, infused knowledge, etc, as well as sanctifying grace. Having lost them by their sin, we do not inherit these divine gifts.

As a result of original sin we thus inherit a fallen nature, deprived of the original holiness and justice, and inclined to evil. This inclination to sin is called concupiscence (an illicit or inordinate desire). St. Augustine and the Christian tradition identify the greatest war we all face as the war between the soul and the flesh. Augustine uses the image of a marriage between the soul and the body; the soul/husband is wedded to the body/wife. Before original sin the soul and body were in perfect union and harmony, whereas now they are at war with each other.

Holy Trinity

In the East, the Greek Fathers (St. Athanasius, St. Basil the Great, St. Gregory Nazianzen, St. Gregory of Nyssa) had already made a thorough presentation of the doctrine of the Holy Trinity during their fight against the Arian heretics. While St. Hilary of Poitiers had initiated the translation of their Trinitarian theology into Latin, it was St. Augustine who affirmed the Trinitarian tradition in the Latin West. He defended the orthodox consensus of St. Athanasius and the Cappadocian Fathers, and further explained it with relational analogies (for instance, the Father being the lover, the Son the loved, and the Holy Spirit the mutual love shared between the two).

The 15 books On the Trinity (De Trinitate), on which he worked for 15 years, are the most profound and elaborate of Augustine’s works.

Celibacy and marriage

Jesus Himself, as well as St. Paul and many Church Fathers, taught that celibacy was the highest calling. Augustine also considered celibacy to be the most blessed state. However, he also defended marriage as good and holy, especially in his treatise The Good of Marriage (De Bono Coniugali).

Today, when marriage is being destroyed not only by the secular governments aided by the mass media, but also by the heretics and apostates who occupy the seats of the Church hierarchy, we need to be reminded of the clarity and unanimity of the teaching on marriage from Jesus, the Apostles, Church Fathers, Doctors, Popes and Councils for nearly 20 centuries. St. Augustine left us several works on the subject. (As a reminder that the doctrine has not changed and cannot change, Casti Connubii, Pope Pius XI’s landmark encyclical on marriage, heavily references the bishop of Hippo.)

Family is the building block of a nation. Marriage is necessary to establish a Christian society. Augustine stressed that God created all humans from one couple, the first bond of human society thus being the union of husband and wife. Sex is not an end in itself but is ordered to the common good of society. Marital sex was a gift to Adam and Eve so that they may fill the Garden of Eden with children and future generations. However, original sin corrupted this gift, and concupiscence causes it to be divorced from its objective of procreation, which ultimately leads to the destruction of Christian society, culture and civilization.

Augustine also affirmed that the union between Christ and the Church was mysteriously signified in Christian marriage. The sacramental bond of marriage sanctions a union that seeks procreation and mutual fidelity.

“These are all the blessings of matrimony on account of which matrimony itself is a blessing; offspring, conjugal faith and the sacrament.” (De Bono Coniugali, cap. 24)

“By conjugal faith it is provided that there should be no carnal intercourse outside the marriage bond with another man or woman; with regard to offspring, that children should be begotten of love, tenderly cared for and educated in a religious atmosphere; finally, in its sacramental aspect that the marriage bond should not be broken and that a husband or wife, if separated, should not be joined to another even for the sake of offspring. This we regard as the law of marriage by which the fruitfulness of nature is adorned and the evil of incontinence is restrained.” (De Genesi ad Litteram, lib. IX, cap.7)

The holy Doctor defended the indissolubility of marriage in several of his works (including On Adulterous Marriages – De Coniugiis Adulterinis, On Marriage and Concupiscence – De Nuptiis et Concupiscentia, The Good of Marriage, etc). He compared the definitiveness and indissolubility of the sacramental marriage bond with the irrevocability of priestly ordination and of baptism. Augustine, in line with all the Church Fathers, affirmed that a married person, even after a separation on account of adultery, could not take another wife or husband.

Other teachings

St. Augustine left more writings about the Holy Virgin Mary than many other early Fathers. He always defended her being the Mother of God (which, though a long-held early Christian belief, only became a defined dogma at the Council of Ephesus in AD 431). He further affirmed her perpetual virginity, writing that she “conceived as virgin, gave birth as virgin and stayed virgin forever”.

The saint also defined the concept of just war. A defensive war would not only be just but may be necessary; peacefulness in the face of a grave wrong that could only be stopped by violence would be a sin.

Augustine’s legacy

St. Augustine is the greatest and most influential among the Church Fathers. His thinking practically established the foundation for Christian civilization; his works inspired the medieval conception of state, empire and Christendom. Charlemagne loved no book more than the City of God, and the Empire he founded was inspired directly by St. Augustine.

As a giant of theology he is only equaled by St. Thomas Aquinas. (St. Thomas himself drew heavily on Augustine; as a Dominican friar he even lived the Rule of St. Augustine, for this was the rule chosen by St. Dominic for his Order of Preachers.)

Of course Augustine’s extraordinary influence is not limited to the realms of theology and philosophy. Nor was he simply an intellectual. Once he had found the Truth he embraced it with all his soul and all his heart, for he understood that Truth must be loved and lived by. While his love was securely rooted in dogmatism (which allows the soul to know what it loves and why it loves), the dogmas were applied in practice, in relation to the duties of Christian life. This combination of heart and mind may explain St. Augustine’s universal influence in all ages. He does not only inspire theologians, he inspires the soul, the inner life of a Christian.

Although some Protestants, by choosing and picking and distorting his words, like to claim Augustine as their own, his Catholic faith and theology come through in all his writings. Like the other Church Fathers, he clearly affirmed the teachings about the Eucharist, praying for the dead, eternal life by merits (i.e. faith and works), etc. He taught about the Divine institution of the Catholic Church, its authority (the God-given authority of bishops and priests as the successors of the Apostles), its essential marks, and its mission in the economy of grace and the administration of the sacraments. Augustine also acknowledged the authority and primacy of the Roman pontiff (“Roma locuta est, causa finita est”, while a paraphrase, came from the bishop of Hippo). And of course there are also his writings about Mary’s purity and perpetual virginity.

Although some Protestants, by choosing and picking and distorting his words, like to claim Augustine as their own, his Catholic faith and theology come through in all his writings. Like the other Church Fathers, he clearly affirmed the teachings about the Eucharist, praying for the dead, eternal life by merits (i.e. faith and works), etc. He taught about the Divine institution of the Catholic Church, its authority (the God-given authority of bishops and priests as the successors of the Apostles), its essential marks, and its mission in the economy of grace and the administration of the sacraments. Augustine also acknowledged the authority and primacy of the Roman pontiff (“Roma locuta est, causa finita est”, while a paraphrase, came from the bishop of Hippo). And of course there are also his writings about Mary’s purity and perpetual virginity.

Augustine’s writings

St. Augustine left us his legacy of thought and teaching in 113 books, 218 letters and some 800 sermons.

While in his own days Augustine was best known for his writings against the heretics (several dozen works refuting the heresies of the Manichaeans, Pelagians, Donatists, Arians, etc), in our times his most popular theological books are those on doctrine, such as On Christian Doctrine, On the Trinity, The City of God. There are also many practical works – helping the faithful live good Christian lives – on a variety of topics such as marriage, continence, virginity, widowhood, lying, patience, etc. The saint also left us many biblical commentaries, sermons and letters.

However, of all of Augustine’s works none has been more universally read and acclaimed than the edifying account of his conversion. In the Confessions (Confessiones) he talks of his journey from the moral abysses of pride and sensuality to his conversion to a life in (and for) Christ. The bishop of Hippo, by his own admission, wrote this autobiography, depicting the struggle between his soul and his passions, for his own humiliation – so that the world which was admiring his holiness may know of all the sins of his youth (as well as the imperfections to which he was still subject).

Augustine sent the finished book to Count Darius with these words: “The caresses of this world are more dangerous than its persecutions. See what I am from this book: believe me who bear testimony of myself, and regard not what others say of me. Praise with me the goodness of God for the great mercy he hath shown in me, and pray for me, that he will be pleased to finish what he hath begun in me, and that he never suffer me to destroy myself.”

In the Confessions we find Augustine’s perhaps most famous lines:

“Late have I loved Thee, O Lord; and behold,

Thou wast within and I without, and there I sought Thee.

Thou was with me when I was not with Thee.

Thou didst call, and cry, and burst my deafness.

Thou didst gleam, and glow, and dispell my blindness.

Thou didst touch me, and I burned for Thy peace.

For Thyself Thou hast made us,

And restless our hearts until in Thee they find their ease.

Late have I loved Thee, Thou Beauty ever old and ever new.”

The City of God (De Civitate Dei), considered by many as the saint’s most important work, was written over a time span of 13 years (AD 413-426). The pagans’ charges that Christians brought about the fall of Rome [more precisely, the sacking of Rome by the Visigoths in AD 410] prompted Augustine to begin writing this work. In the first part (the first ten books) he refutes the charge and demolishes pagan beliefs. In the second part (books XI-XXII) he shows the two cities – the heavenly city (City of God) and the earthly city (City of Man or City of the Devil) – from their origin, through their growth throughout history, to their final destinations.

Augustine conceives human history as a battle between the City of God, i.e. the followers of Christ and His Church (the sons of light who love God and dedicate themselves to His eternal truths) and the City of Man (the sons of darkness immersed in their self-love, pride and the pleasures of this world). The destiny of the inhabitants of the City of God is eternal happiness, while those who follow the Devil are destined for eternal punishment. Augustine expounds on questions such as the existence of evil, the suffering of the just, original sin, concupiscence, free will, etc. He stresses that the true home of a Christian is heaven; hence it is not an earthly kingdom but heaven to which his affections and efforts should be directed.

The Enchiridion (or Handbook on Faith, Hope and Love) is a synthesis of Augustine’s theology reduced to the three theological virtues.

The various letters we have from St. Augustine tell us about his life, work and doctrine. In a letter to Count Boniface the holy bishop gave this valuable advice (which he himself, once converted, never failed to live by): “If you consult me for the salvation of your soul, I know very well what to say: Love not the world, neither the things that are in the world.”

St. Augustine, the penitent – a model to imitate

St. Augustine, the holy Doctor, the pillar of the Church, may be a distant giant of Faith and theology – one whom we can admire in awe but whose example we could never hope to imitate. But there is another Augustine – Augustine the penitent – who speaks to and is understood by each and every soul.

His is the story of a great sinner who – despite having one of the most brilliant minds humanity has ever known – spent the first half of his life wallowing in impurity and false beliefs, to become not only one of the greatest saints but also an extraordinary defender of the faith he had earlier so scornfully rejected.

It is also the story of his mother, St. Monica, who – by her incessant prayers, tears and suffering over so many years – obtained from God the grace for her son to abandon his evil life and to give himself entirely to God. And, most importantly, it is a magnificent proof that God’s mercy and goodness is infinitely greater than our wickedness and sinfulness, and that He never gives up on a lost sheep who is trying to find the way back to Him. All He wants is a sinner’s repentance. No matter how much we may have offended God, if we come to Him with contrite heart, determined to amend our ways, He will not only welcome us with open arms but will give us all the graces we need to become saints.

Let Augustine’s example be an inspiration and a warning. An inspiration to all who struggle to overcome a vice or sin; a warning to a world addicted to lust and impurity. It was the sins of impurity, along with his pride, that darkened Augustine’s mind to the point he could no longer see or understand the Truth. Let us then take to heart this lesson: sin blinds us; it darkens the intellect, it weakens the will. [Or are we moderns wiser, more “enlightened” than the great St. Augustine? Do we know better? Do the eternal truths no longer apply to us?]

“Too late have I loved You”, cried Augustine to God. But once he had obtained the grace of conversion he made up for it by the holiness of his life – because he didn’t waste any time but gave himself entirely, heart, body and soul, to God and to the service of Him and of His Church. In this sense we are all called to follow in St. Augustine’s footsteps.

Sancte Augustine, ora pro nobis!

—

Life of St. Augustine (St. Possidius) – audiobook; or read online here [an early biography written by Augustine’s friend Possidius, telling us about the saint’s life and apostolate]

The Life of St. Augustine, Bishop, Confessor, Doctor of the Church (P. E. Moriarty) – pdf, text, kindle

The Confessions of St. Augustine (St. Augustine of Hippo) – text, kindle format; also here in pdf, text, audio

The City of God (St. Augustine) – text, kindle format; also here in pdf, text, audio

Handbook on Faith, Hope and Love (St. Augustine) – pdf, text, audio

Soliloquies (St. Augustine) – pdf; or pdf, text, kindle format here

—

Pavia is also home of the Collegio Ghislieri – a college founded in 1567 by Pope St. Pius V (Antonio Michele Ghislieri). A majestic statue of the holy Pope stands in front of the college at Piazza Ghislieri. Another statue of his can be found in a corner of the college courtyard, and at the entrance/reception hangs his portrait.