Bosco Marengo and Rome: Saint Pius V

Casa Natale di S. Pio V (Bosco Marengo; for guided visits contact:info@amici-di-santacroce-di-boscomarengo.it; amici-di-santacroce-di-boscomarengo.it/visita/visita.htm)

Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore (Piazza S. Maria Maggiore 42, Rome; Mon-Sat 7am-7pm, Sun 9:30am-12:30pm; website)

Bosco Marengo, the native village of St. Pius V, is situated approximately 10 km from the town of Alessandria, and 82 km from Milan. There are several daily trains from the Milano Centrale station to Bosco Marengo via Alessandria. (The journey from Milan to Alessandria takes about 1h 20min; the second train, leaving from Alessandria, reaches Frugarolo-Bosco Marengo in about 7 minutes.) You could even fit in Pavia, the final resting place of St. Augustine, in the same day trip. Bosco can also easily be reached by train from Turin or Genoa.

The native home of the great Pope can still be seen in Bosco Marengo. If you are interested in visiting, contact the very friendly locals from the Association of the Friends of Santa Croce (email: info@amici-di-santacroce-di-boscomarengo.it or tel:(+39) 0131-299342, cell: (+39) 331-4434961).

Having scheduled my visit by emailing them, they’ve picked me up at the local train station of Frugarolo-Bosco Marengo, and graciously showed me all the places of interest in Bosco: the native home of St. Pius V; the church San Pietro al Bosco where one can still see the original baptismal font where Antonio Ghislieri, future Pope Pius V, was baptized in 1504; the former Dominican convent of Santa Croce which he built, etc.

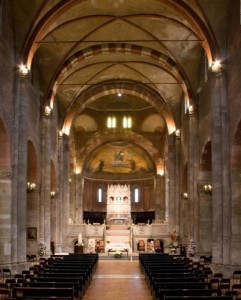

There are many other locations in Italy connected to St. Pius V. The most important is the Basilica Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome which houses his tomb (in the Sistine chapel, in the right transept). See photos towards the end of this post. (The Basilica is also home to the Holy Crib relic and the famous icon of the Blessed Virgin known as Salus Populi Romani.)

In the Dominican convent and Basilica of Santa Sabina, on the Aventine Hill in Rome (Piazza Pietro D’Illiria 1, Rome; 7:30am-12:30pm, 3:30-5:30pm) one can see the former cell of St. Pius V, with a number of paintings showing famous scenes from his life, as well as the convent museum preserving several relics of the saint. Also in Rome, in the Dominican convent and Basilica of Santa Maria sopra Minerva (Piazza della Minerva 42, Rome; santamariasopraminerva.it) is a chapel of St. Pius V with paintings of various episodes from his life. (The same basilica also houses the tombs of St. Catherine of Siena, Fra Angelico, and Pope Paul IV.)

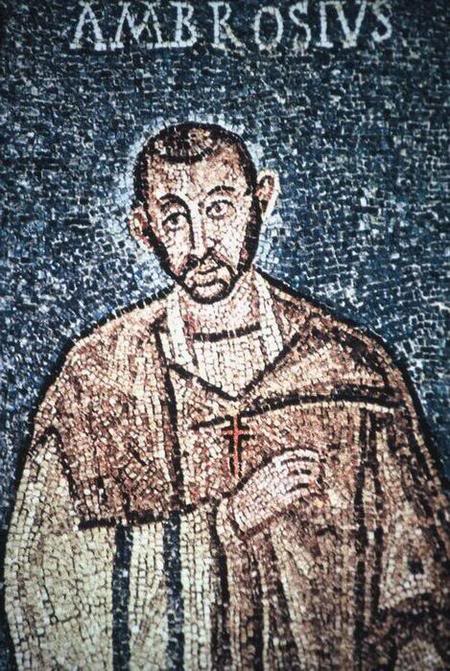

SAINT PIUS V: MONK, INQUISITOR, POPE, DEFENDER OF EUROPE AGAINST THE TURKS

The Church was in deplorable condition when Pope St. Pius V was elected to the throne of Peter in 1566. It was a time of moral laxity and spiritual confusion. Concessions to heretics and lukewarmness of the Catholic authorities had allowed Protestantism to spread in Europe. At the same time Christendom was in imminent and deadly danger from the Ottoman Turks who were already dominating the Middle East, North Africa, the Mediterranean and the Balkans.

The Church was in desperate need of a holy, zealous, uncompromising and fearless Pope. It got him in St. Pius V – one of the greatest Pontiffs of all times – who in his short but glorious six year reign reformed discipline and morality of the Catholics, wiped out heresy in Italy, implemented the decrees of the Council of Trent, issued the Catechism, promulgated the Roman Missal, excommunicated Elizabeth I, and saved Europe from the Mohammedan menace.

From shepherd boy to Dominican friar

Antonio Michele Ghislieri was born and baptized on January 17, 1504, in the little village of Bosco, near Alessandria. He was baptized with the name Anthony but later took the name of Michael in honor of the Archangel St. Michael whom he chose as his patron. His pious parents, though poor, were of ancient and noble family.

Little Anthony loved to be alone. His greatest delight was to be in church, praying the Rosary and hearing Mass daily. His desire was to become a religious but his parents were too poor to afford him the studies. One day, as he was tending sheep, he saw two Dominican friars passing by. A conversation ensued and the friars, touched by the boy’s simplicity, candor, intelligence, and his angelic aspect, offered to take him with them to their convent, if he could get his parents’ consent. Thus it was that 14 year old Anthony entered the Dominican monastery at Voghera. [Other sources state that a well-off neighbor paid for him to study with the Dominicans.] He made remarkable progress in his studies and after two years was allowed to take the habit of St. Dominic. The following year (1521) he made his solemn profession in the convent of Vigevano. It was on this occasion that he assumed the name Michael, becoming Brother Michael of Alessandria.

His superiors sent him to the University of Bologna to take his degree in theology and philosophy. At just 20 years old he was appointed professor of philosophy, and then theology, which he continued to teach for 16 years. Ordained to the priesthood in 1528, he went to his native Bosco to celebrate his first Mass. Upon arrival he found the village burnt down, his home half destroyed and the parish church desecrated by the French imperial troops. His parents took refuge in nearby Sezze, which is where he said his first Mass.

Fr. Michael spent the next 15 years in various monasteries of his Order, and was elected prior four times. His rule was severe but his strictness was coupled with kindness. To his religious he preached rather by example than by word, by his great piety, his scrupulous and most exact observance of the Rule, his severe mortifications and rigorous fasting. His days were spent working for souls, and the greater part of the nights in prayer. Reading and study were his favorite recreations. Daily he read the lives of the saints, and was fond of studying the works of St. Thomas Aquinas, to whom he was devoted, as well as those of the Fathers and Doctors of the Church.

The saintly prior never used dispensations from the Rule usually granted to those preaching and teaching, nor did he easily grant them to others. No one would be allowed to absent himself from the Divine Office, or to go out of the convent without some urgent necessity. For, as he explained: “As salt dissolves when it is thrown into water and becomes indistinguishable from it, thus the religious (by the grace of God the salt of the earth) assimilates with fatal eagerness the maxims and spirit of the world, when he begins to spend his time in a number of unnecessary visits.” When he did have to leave the monastery on some priestly duty, he always journeyed on foot, even when he went to preach in distant towns.

Inquisitor, defender of the Faith

At that time war and discord were everywhere, and false teachings were spreading throughout many parts of Europe. The Calvinist and Lutheran heresy was gradually seeping from Switzerland and Germany into northern Italy. The Turkish invasion was also a constant danger, especially in southern Europe.

In 1542 Pope Paul III reconstituted the Roman Inquisition in order to stop the influx of heresy. When the Holy Office requested that the Dominicans provide the best man they had to serve as Inquisitor at the important outpost of Como, the Provincial nominated Father Michael Ghislieri who by then was already known for his holiness, firm doctrine, and great zeal for the salvation of souls.

Thus in 1543 the future Pope Pius V became Inquisitor at Como and in the heresy-infected Swiss Grisons. One of his main concerns was to stop the traffic of heretical books from Switzerland to Italy. For six years he spent days and nights traveling through each town and village, often in danger of assassination (he escaped many ambushes that were laid for him), combating the sale and publication of heretical and immoral texts, doing his best to lead heretics back to the Faith, and warning the simple folk against the danger to their souls. Fr. Ghislieri, having before his eyes only the honor of God and the good of souls, was fearless; indeed he was fully prepared to lay down his life for the Faith, as St. Peter Martyr (another Dominican Inquisitor, murdered by heretics) had done. Neither flattery, nor threats, nor bribes had any influence on him.

[Modern critics of the Inquisition, aside of not believing in what the Faith teaches us about the salvation and damnation of souls – for if they believed, they would recognize and understand the need to combat heresy which leads souls to hell – completely disregard the customs and laws of the 16th century.

What is today called “religious liberty” – i.e. the supposed right of everyone not only to privately believe but also to preach and teach his own opinions about Revealed Truth, however false or repugnant those opinions may be to the doctrines of the Church – was utterly unknown in the 16th century. There was only one Church throughout Christendom, with the Pope at its head. The Church was acknowledged by all as a spiritual kingdom founded by Christ, teaching and ruling by His authority; all men considered it the duty, not only of the Church but also of the secular government, to prevent heresy from being preached or disseminated by books. As only one Church and one revealed doctrine was accepted and recognized, it was considered high treason against God and the authority of the State to teach and spread false doctrine. (So too everyone knew the inevitable consequences of certain acts, such as the penalties for heresy. And not just heresy; for instance, the civil penalty for blasphemy in Spain, Italy, France, Germany, England, etc, was death.)

The Inquisition was governed by men of great learning, justice and prudence, even saints in many cases. It was perhaps the first judicial institution to provide ample safeguards for the rights of the accused. Those accused of heresy were given an extensive trial, with every chance to repent. If they continued recalcitrant they were handed over to the State which imposed the penalty for violation of the civil laws. It’s also important to note that while the Inquisition only used torture in relatively rare cases and with strictly regulated precautions, all civil governments throughout the world used it, ever since the pagan times, and without precautions. In those times, free from the sentimental humanitarianism of our age, it was understood by all what the consequences of certain crimes were.]

Fr. Ghislieri was uncompromising with those involved in spreading heresy, and didn’t hesitate to punish and excommunicate them, even when they were wealthy, noble or holding prominent positions and offices – whether civil or ecclesiastical (as was the case of the bishop of Bergamo who had secretly become a Lutheran). He was threatened with death on many occasions, and was even stoned in the streets of Como after disrupting the commerce of heretical books run by a wealthy and influential local merchant.

Always resigned to the will of God, the Inquisitor was traveling on foot, alone and armed only with his staff and breviary. On one of his missions in the Swiss Grisons, when he had to pass through a district where he was particularly disliked, he was advised to lay aside his habit and travel in disguise. He refused, saying: “When I accepted the office of Inquisitor I also accepted almost certain death. For what more glorious reason could I die than because I wear the white habit of St. Dominic?” Many were won over by his humility, simplicity and purity of motive – his ardent love of God and zeal for the salvation of souls.

In 1551 Michael Ghislieri was appointed by Pope Julius III Commissionary-General of the Inquisition. Based in Rome, one of his daily duties was to visit in prison those accused of heresy. He went among them as a true father, and never spared any effort to gain them for the Faith. Thanks to his charity, patience and holiness he succeeded in making many – though not all – renounce their error and return to the Faith.

One of his most famous cases was that of Sixtus of Siena – a young Jew who had become a Catholic and a Franciscan friar. He became a popular preacher but was soon influenced by heretical doctrines. Arrested and imprisoned, he abjured his heresy, was released and returned to his Order. After beginning to preach again he relapsed into heresy, and was convicted. The penalty for a relapsed heretic was death by fire, so there was no hope. Father Michael visited him in prison every day and spoke to him kindly as a friend, while also praying, fasting and offering daily Mass for his conversion. Eventually Sixtus became conscious of the enormity of his sin and, knowing he had disgraced his Order, wanted to expiate his shame by death. The Inquisitor, deeply touched by his repentance and misery, suggested that he might better expiate his guilt by living a life of penance. Ghislieri then went to the Pope and begged and obtained pardon for the young friar. Sixtus made abjuration of his heresy, was pardoned and released, and admitted (by the Inquisitor himself) into the Dominican Order. Sixtus of Siena went on to become one of the greatest Scripture scholars of his century, and was never tired of saying that he owed both his temporal and eternal salvation to Michael Ghislieri.

Cardinal of God

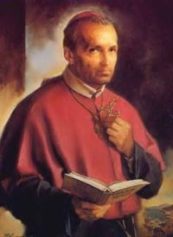

In 1555 Cardinal Carafa, who had a deep affection and admiration for the saintly Dominican, was elected Pope under the name Paul IV. The new Pope, knowing Fr. Michael’s desire to remain a simple religious, commanded him, by holy obedience, to accept whatever office or dignity might be laid upon him, for the good of the Church. The following year Michael Ghislieri was consecrated Bishop of Nepi and Sutri, near Rome. In 1557 Paul IV made him Cardinal, under the title of Santa Maria sopra Minerva. (He would be known as Cardinal Alessandrino, after the city nearest to his place of birth.)

Paul IV had great esteem for his friend who was not only holy, wise and learned but also utterly free from ambition, inspired solely by the desire to serve God and His Church. Cardinal Alessandrino’s advice, never given unasked, was always accepted by the Pope. In 1558 Paul IV conferred upon him a unique office which he would be the first and last to hold. He became the Grand Inquisitor of all Christendom; his authority was final and without appeal. (After his resignation no one else was trusted with so important an office, and the authority reverted again to the cardinals of the Holy Office, for “there were not two Cardinal Alessandrinos.”)

The saint’s life continued as austere as it had ever been. Except on state occasions, when obliged to put on his cardinal’s robes, he wore the rough white habit of a simple Dominican friar. His meals (never more than two daily), his rule of life, his fasts, penances and prayers – all remained unaltered. His usual food was bread and boiled herbs (chicory). About this time he started to be plagued by a serious internal complaint causing him severe and often excruciating pain, which was to last as long as he lived.

He employed as few servants as possible, and chose them scrupulously, admitting only those of most exemplary piety. He gave them a rule of life and treated them as his children rather than servants. The simple and austere life of Cardinal Alessandrino was in sharp contrast to the princely style in which most cardinals then lived. Yet his simplicity and humility won the respect and even affection of his fellow cardinals, many of whom would come to imitate his example. He never allowed any abuse of his new dignity. To requests for advancement coming from relatives he turned a deaf ear, saying that he would never enrich his kinsfolk with the goods of the Church, and advising them to care about increasing in virtue rather than wealth.

In 1559 Paul IV died and Giovanni Angelo Medici was elected Pope, taking the name of Pius IV. The friends and favorites of the late Pontiff fell in disfavor, and Cardinal Alessandrino was appointed bishop of the distant diocese of Mondovi. He found his new diocese in a deplorable state, owing to lax and non-resident bishops, and set to restore purity of faith and discipline, exhorting priests and religious to live holy and blameless lives. He also paid a visit to Bosco, his native village, where he laid the foundation for a large Dominican convent (Santa Croce).

In 1560 he was summoned back to Rome where Pius IV was anxious to complete and put in practice the decrees of the Council of Trent (1545-1563). Yet Cardinal Alessandrino, with his unflinching zeal and disregard for human respect, soon came into collision with Pius IV when the latter announced his intention to promote a 13 year old relative to the dignity of cardinal. When the German Emperor Maximilian II requested the Pope to allow priests to marry, under the pretext that this might facilitate the return of heretics to the Faith, it was Cardinal Ghislieri who spoke most vigorously against the abolition of the holy and ancient canon of celibacy. The saint’s permanence in Rome finally became untenable when he once again opposed the Pope, pointing out that Pius IV’s plan to settle a pension upon his favorite nephew out of the funds of the Sacred College would be a misuse of Church property. However, before the good Cardinal could return to Mondovi Pius IV fell ill and died.

Shepherd of Christendom

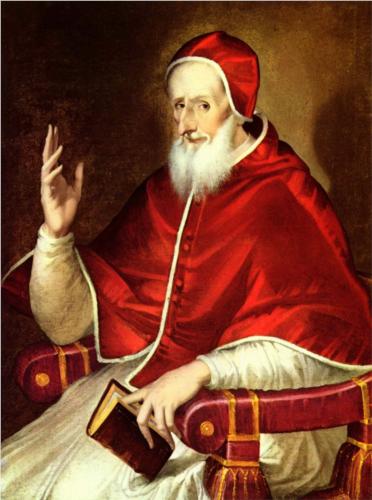

The ensuing conclave had dragged on for over three weeks when Cardinal Borromeo, having despite his young age the most influence in the Sacred College, convinced the other cardinals to choose Cardinal Alessandrino who, in his view, “would govern the Church gloriously.” His election came as a great surprise for he had not campaigned for it, had neither court nor wealth, entered into no pacts, made no promises, and had no Catholic nation behind him (in fact when the Emperor Maximilian heard that a monk had been elected he made fun of him). The new Pope, instead of taking the name Paul, after his friend and protector Paul IV, out of regard for Charles Cardinal Borromeo chose the name of the latter’s uncle, Pius – his first act of self-abnegation as Pontiff. He was crowned in St. Peter’s Basilica on January 17, 1566, on his 62nd birthday.

Many Romans – especially the lax, the sinful, and the adherents of the new heretical sects – were worried that such a strict and austere man had been elected. Thus it was that the saint remarked that he hoped to govern in such a way that the grief felt at his death would be greater than the grief felt at his election.

Pius V had a three-fold labor to perform: to fight for the purification of the Church, to keep Europe Catholic and united against the Turks, and to help save men’s souls. To these ends he devoted all his strength, daily crucifying his frail body.

The reforms began from the very day of his coronation. Instead of spending money on the habitual celebrations and banquets he distributed it among the poorest families and poor convents. One of his first acts was to dismiss the Papal court jester. St. Pius V started with a reform at home, first in his own household, making it a model of virtue, then among his cardinals whom he exhorted to moderation and holiness, making it clear that the luxurious habits of princely living which had been encouraged by the Renaissance Popes would find no favor with him: “You are the light of the world, the salt of the earth! Enlighten the people by the purity of’ your lives, by the brilliance of your holiness! God does not ask from you merely ordinary virtue, but downright perfection!”

Soon after his election Pius V set out to restore order and beauty to Rome. He repaired sacred buildings, aqueducts and the city’s fortifications, set up free schools, provided housing for beggars and assigned priests to instruct them in Christian faith and morals. He supervised the appointment of magistrates and ensured they administered justice fairly. Imprisonment for debt was forbidden. Seeing the number of unemployed in Rome, the saint started public works for their benefit. Nor did he spare any effort and expense to ransom Christian slaves from the Turks. (Well over a million of European Christians were captured and taken as slaves by the Mohammedans in the 16-17th cent.)

While the Pope himself continued to live the austere and penitential life of a poor Dominican friar, his generosity to the poor and suffering was legendary, whether they be impoverished priests, the poor families of Rome, or the exiled English Catholics who were flocking to the Eternal City. In 1566, when Rome was ravaged by plague and famine, Pius V organized a distribution of money, food (having bought wheat from Sicily at his own expense), medicine and clothing, and paid for a large staff of doctors to attend the sick. He appointed priests to hear confessions of the dying and to bury the dead, and often went himself to comfort the sick and prepare them for death.

From the very beginning of his Pontificate St. Pius V strove to improve public morals, banishing from Rome men and women of bad character, as well as Jewish usurers. Moral offenses were punished severely. Prostitutes were expelled from Rome and the Papal States, unless they agreed to marry or enter a convent. Sodomy was punished with death. (Note also St. Pius’ Constitution Horrendum Illud Scelus on priests guilty of this crime.)

The holy Pope zealously watched over the sanctity of family life. He acted against adulterers who, without distinction of status and rank, were publicly whipped, imprisoned and, if not corrected, banished from the city. He also forbade the employment of young girls as servants, to safeguard their virtue and purity. Strict regulations were imposed upon taverns and similar establishments. The Papal States were also swiftly freed from the plague of bandits and robbers who were executed whenever they were seized.

A Bull was issued against irreverence in churches, demanding piety, silence, and modesty in dress. Strolling, chatting, laughing and whispering in church were forbidden as offending God in the Blessed Sacrament. Disturbance of divine worship, blasphemy, and profanation of Sundays and Holy Days carried drastic penalties.

In less than a year the city changed so completely that it was remarked that the Pope, with his strict regime, had turned Rome into a monastery. A German nobleman, writing of the astonishing piety and penitence witnessed among the Roman population, concluded: “…But nothing can astonish me under such a Pope. His fasts, his humility, his innocence, his holiness, his zeal for the faith, shine so brilliantly that he seems a second St. Leo, or St. Gregory the Great… I do not hesitate to say that had Calvin himself been raised from the tomb on Easter Day, and seen this holy Pope… in spite of himself he would have recognized and venerated the true representative of Jesus Christ!” The people of Rome, impressed by his goodness and holiness, soon began to love him as a father. The Spanish ambassador stated that for three hundred years the Church had not had a better head, adding: “This Pope is a saint.”

Perhaps most importantly, St. Pius V set out to reform the discipline among the clergy. All bishops were ordered to return to their sees, to live there, and to become true fathers of their people. He trained young and deserving priests for the office of bishop, and appointed them all over the world. Seminaries were established everywhere. To all clergy he upheld the standard of perfection. All priests who heard confessions were examined to ensure their doctrinal and moral soundness. The decrees of Trent were to be rigorously observed by all priests and religious. Simony was punished severely. Strict regulations were made for all religious houses and enclosure was imposed upon convents (in accordance with the Council of Trent). Divine Office had to be recited in every church.

Pius V’s chief concern was the salvation of souls, and to this he subordinated all other considerations, both at home and abroad. He was a great supporter of the missions, especially in South America and the Indies. Knowing that the lack of instruction in the Faith was the principal cause of the disorders afflicting the Church, he ordered catechism classes to be taught to children on Sundays, and exhorted all bishops to do likewise in their dioceses. He made all Jews listen to sermons preached by Dominican priests, and converted many to the Faith. Whenever possible he liked to baptize them by his own hand. One of them was the distinguished rabbi of Rome, Elias, who, along with his three sons, was baptized by the Pope in the presence of a great multitude. His conversion was followed by that of many others.

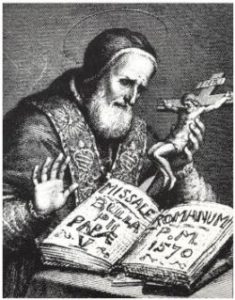

In 1566 the Catechism of the Council of Trent (the Roman Catechism) was published under St. Pius’ direction. He also had it translated into French, Italian, German and Polish. Two years later came the new edition of the Breviary, and in 1570 the revised Roman Missal.

In 1570 St. Pius V, in the Bull Quo Primum Tempore, promulgated the Roman Rite (Tridentine Mass) to be celebrated throughout the Latin Rite of the Church in perpetuity. Pius V did not introduce a new rite of Mass. Rather, in accordance with the decree of the Council of Trent calling for a uniform Missal to be used by all Latin Rite Catholics, he took the Missal that had been in use in Rome and many other places – i.e. the rite of Mass that all the Popes had used and that dates back to the Apostolic Tradition – and, cleaning it of certain innovations that had crept in over the centuries, extended it to the whole Church (of the Latin Rite). An exception from the obligatory use of the Roman Missal was permitted for rites which, approved by the Apostolic See, had been in continual use for at least 200 years. (Thus the Benedictines, Carthusians, Cistercians, Carmelites, and Dominicans were allowed to keep their ancient rites and breviary, and the Ambrosian rite of Milan and the Mozarabic rite of Toledo were also retained.)

In a reform of Church music, which had become almost operatic in its extravagantly secular character, the old Gregorian plain-chant was restored to its splendid simplicity. (St. Pius V appointed Palestrina master of the Papal chapel and choir.)

For Pius V questions of Faith took precedence over any other business. Knowing that heresy kills the soul, the saint, who had spent a good part of his life as a Dominican friar and Inquisitor trying to extirpate it, continued the good fight as the Father of Christendom, in particular against the Lutherans, Calvinists and Huguenots. England, Scandinavia, Switzerland and parts of Germany had already collapsed to heresy. When France was plagued by continual rebellion, violence, outrages and sacrileges committed by the Protestant Huguenots, it was St. Pius V who sent both money and soldiers to defend the eldest daughter of the Church, thus safeguarding her from falling to the heretics.

In 1570 St. Pius V issued a Bull of Excommunication and Deposition against Elizabeth I of England. Both his predecessors and St. Pius V had tried every means in their power to convince Elizabeth to return to the Faith and Church, yet all the appeals, entreaties, arguments and prayers had been in vain. In the end the only course of action left was for the Pope to excommunicate the apostate Queen – i.e. to formally declare her to be outside of the Catholic Church, thus absolving her subjects from their allegiance (her commands could not bound in conscience those over whom she no longer had any right to rule). [This was an ancient and universally recognized principle of medieval Christian States.]

[Elizabeth had been crowned by a Catholic prelate, with Catholic rites, and had taken the oath of Catholic sovereigns, pledging to govern as a Catholic Queen and to protect and defend the Church, the bishops, and their canonical privileges. Shortly thereafter she repudiated Papal authority, made herself head of the Church of England, prohibited the Mass, imprisoned and exiled Catholic prelates. Catholics were persecuted and killed, priests were drawn, hanged and quartered. Protestantism became the state religion of England, and was forced upon the population by the rope and knife. After the Northern rising in defense of the true Faith (and for the release of Mary Stuart, the Catholic Queen of Scotland imprisoned by Elizabeth) was defeated, and thousands of Catholics were tortured and butchered, St. Pius V hesitated no longer and signed the Bull of Excommunication.]

Defender of Christendom

The Ottoman Turks had been the scourge of Europe for four long centuries. Under Suleiman II, the Magnificent (1520-66), Turkish dominions in Asia, Africa and Europe had increased alarmingly. Belgrade fell to the Turks in 1521, Rhodes the next year. Then the heart of Hungary became a Turkish province, and Vienna was besieged. Countless Christian slaves had been captured. Hundreds of thousands of Christians had been tortured and slain.

Suleiman’s first check was in 1565 at Malta. The Grand Master of the Knights of St. John, Jean de Valette, courageously defended the besieged island with his 500 knights and a few thousand Maltese men against an Ottoman army of over 40,000. The Turks were temporarily driven away but the defenders of Malta, having neither money nor men to repair the ruined defenses, decided to abandon the island. St. Pius V commanded them to remain at this outpost of Christendom, and sent Valette the money necessary for the rebuilding of the fortifications, thus saving Malta.

Suleiman then attacked the commercially important island of Chios, sacked the city and massacred the entire population. He also organized an army of some 100,000 men to march through Hungary toward Vienna, though the campaign ended at the Siege of Szigetvár. (Szigetvár eventually fell after heroic defense by Count Miklós Zrínyi and his men, outnumbered by the Turks fifty to one. To the last man the Hungarian knights died defending Christian Europe; all civilians who had survived the siege were slaughtered by the Turks.) St. Pius V ordered the Forty Hours devotion in Rome, public prayers, and three great processions in which he himself took part. On the day of the third procession Suleiman II (who was said to fear the prayers of the Pope more than his armies) died.

Suleiman II was succeeded by his son Selim II, nicknamed “the Sot”, who inherited his father’s ambition to conquer Rome and destroy Christianity. He demanded that the Venetians, who had a commercial treaty with the Turks, give him Cyprus. (Cyprus, the most important island of the Mediterranean, belonged to Venice.) The capital Nicosia was besieged by the Turks and upon surrendering was sacked. 20,000 inhabitants, including their bishop, were massacred (total annihilation being the usual method employed by the Mohammedans). Cyprus had fallen to the Turks, with the exception of Famagusta which, under its governor Bragadino, was heroically resisting a long siege and numerous Turkish attacks. For ten long months the besieged city had withstood the Turkish forces but the inhabitants were dying of starvation as there was no food left in the city. Thus in August 1571 Bragadino accepted the Turkish offer that all population would be spared if the city capitulated. As soon as the deal was made the Turks broke the terms and massacred the entire population. Bragadino’s ears and nose were cut off, his nails torn out, his teeth broken; he was stripped, flogged and, after eight days of barbaric torture, flayed alive.

St. Pius V had been trying ceaselessly, ever since his accession, to unite Europe against the Mohammedan enemy threatening the extinction of Christianity. Yet political rivalry, jealousy and commercial interests prevented most nations from joining the defense League against the Turks proposed by the Pope. (England made an alliance with the Turks, while France had an extensive commercial treaty with them and was willing to jeopardize Christendom for her own immediate advantage. Emperor Maximilian, rather than heeding the Pope’s call for a new crusade, was more interested in ending the disputes in his own states by trying to please both Catholics and Protestants.)

Finally, after five years of Pius’ pleading with the Christian kings and princes, the Spanish and the Venetians agreed to join in. On May 24, 1571, the Holy League was signed and sworn to by the Pope, the King of Spain and the Venetian Republic. Don Juan of Austria, the illegitimate son of Charles V and half-brother of Philip II, King of Spain, was chosen to lead the League. While only 24 years old, he had already distinguished himself in war with the Moors. Spain’s fleet was under the command of the Genovese Gianandrea Doria. Marcantonio Colonna commanded the Pope’s fleet; Sebastian Venier and Agostin Barbarigo the Venetian one. The Pope was to pay one sixth of the cost of the crusade (but in the end actually paid almost 60%), Spain three sixths, and Venice two sixths. St. Pius V emptied the Papal treasury; his subjects, rich and poor, followed his example and donated generously. (All offerings were voluntary; the Pope rejected the suggestion of the imposition of a special tax on the people.)

St. Pius placed the expedition under the protection of the Queen of the Holy Rosary. The Rosary was to be daily recited on each ship; those left at home were also to pray it each day to storm Heaven for the success of the League. The Pope extended the devotion of the Forty Hours and ordered public prayers and processions in which he himself took part.

The saint knew that God would only defend the Christian forces if they proved themselves worthy by uniting for His greater glory and for the preservation of Christendom. He therefore ordered that any men who were either living scandalous lives or were only interested in plunder be removed from the Christian ships, for God’s assistance was of infinitely greater value than that of a few additional men. No women were allowed aboard the vessels. Blasphemy was to be punished by death.

Don Juan and his men fasted for three days. The entire crew confessed and received Holy Communion. St. Pius V granted a plenary indulgence to the soldiers and crews of the Holy League. Priests of the great Orders, Franciscans, Capuchins, Dominicans, Theatines and Jesuits, were stationed on the decks of all the Holy League’s galleys, offering Mass and hearing confessions. Don Juan gave every man in his fleet a weapon more powerful than anything the Turks could muster: a Rosary.

The Turks had just ravaged Dalmatia (then belonging to Venice) and several islands, taking over 15,000 Catholic slaves. On September 20 Don Juan, heading the fleet composed of Spanish, Venetian, Papal and Genovese galleys, along with those of the Knights of Malta who generously sent all their men, sailed from Messina (Sicily). Moments earlier the Papal Legate gave the Apostolic benediction to the 60,000 kneeling men.

Back in Rome, and up and down the Italian Peninsula, at the behest of Pius V the churches were filled with the faithful praying the Rosary. In Heaven, the Blessed Mother was listening. Though the Turks outnumbered the Christians, were more experienced, and had never been defeated by sea, St. Pius had perfect confidence in Divine Providence.

On October 6 the Christian fleet received the news of the fall and destruction of Famagusta and the sadistic torture and murder of its heroic governor Bragadino. On October 7 the two fleets finally came face to face in the Bay of Lepanto, off the coast of Greece. On each Christian ship the Rosary was recited for the last time, and priests gave the men general absolution. At the same time in the Vatican the aged Pope, worn out by fasting and austerities and broken by illness, was kneeling in prayer as he had done almost uninterruptedly since the fleet had sailed.

The wind, initially favoring the Muslim fleet, suddenly stopped and reversed. Don Juan threw himself upon his knees and prayed. All the soldiers and sailors did likewise, while the priests held up the crucifixes. Then the young commander stood up and, unfurling the Holy League’s blue banner bearing the image of Christ Crucified (a gift of St. Pius V), gave the order to attack. The battle lasted less than five hours. By 4:30 pm the League had secured a victory. The Turks lost 240 ships and some 33,000 men – including admiral Ali Pasha (out of a fleet of 330 ships and over 85,000 men); the Catholics lost about 10,000 men and 12 (of 212) vessels. 15,000 Christian slaves were set free.

At the moment the battle was won St. Pius V, who was with his Pontifical treasurer, suddenly rose, opened the window to the east, and stood for a few moments gazing into the sky. Then he cried out: “Let us set aside business and fall on our knees in thanksgiving to God, for he has given our fleet a great victory!” These words of the holy Pope, immediately written down, repeated to the cardinals, signed and sealed but not yet published, were only confirmed two weeks later when the messenger, delayed by storms, arrived at last with the news of the victory.

Masses of thanksgiving were celebrated, solemn Te Deums and processions took place; the people acknowledged that the victory was of God, through His Blessed Mother and His Vicar on earth. St. Pius V made October 7 the Feast of Our Lady of Victory, in honor of Her who had saved Christendom. Gregory XIII changed the title to Feast of the Holy Rosary (in 1573). Pius V also added to the Litany of Our Lady of Loreto the title “Help of Christians.” [Let us remember Lepanto when we pray “Auxillium Christianorum, ora pro nobis!”]

St. Pius V placed the flagship banner of the Ottoman admiral Ali Pasha – the famed “Banner of the Caliphs” treasured by Ottoman sultans – in the Lateran Basilica for all to see. (The wretched Paul VI gave it back to the Turks in 1965, thus renouncing not only a crucial Christian victory but also the prayers and sacrifices of the great Pope and saint.)

Lepanto – the most important naval battle in history – was a turning point for Christendom. It saved Christian Europe and ended the Ottoman Empire’s dominance of the Mediterranean. Never again did the Muslim fleet pose a real danger to Europe (although the Mohammedans did keep expanding their bases on the African coast and harassing European ships and territories across the Mediterranean).

St. Pius V urged the Christian powers to follow up this great victory by joining the Holy League, not only to free Europe for all time from the Muslim menace but to liberate Constantinople and Jerusalem as well. The indefatigable old warrior-saint had the crusading spirit burning within him until his last moment. (Unfortunately, after his death the Holy League fell apart. The rivalries among the Catholic powers and their preoccupation with domestic concerns prevailed. Venice made a truce with the Turks; France proposed an alliance with the sultan.)

The Christian victory at Lepanto, by arresting the danger of Mohammedan invasion, made possible the survival of the greatest civilization mankind has ever seen. Our forefathers fought heroically and laid down their lives in defense of God, the Faith, the Church and their homeland. In our own ignominious days Europe, having rejected her Christian faith and heritage and become seeped in depravity, insanity and self-hatred, is herself inviting and welcoming the invaders who once again come to butcher, rape, and subdue her.

Spiritual life and virtues

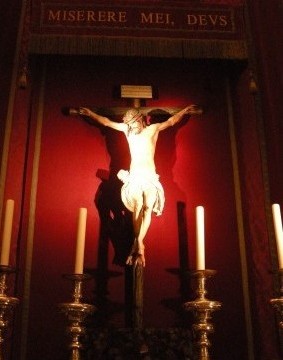

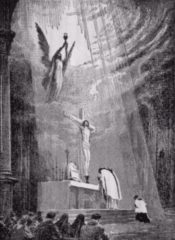

The virtues St. Pius had displayed as a monk and bishop he continued to practice after his election to the Seat of St. Peter. He held in great balance his life of prayer and life of action. His love of true doctrine was matched by his fervent devotion. A Crucifix stood always before him on his desk, at the foot of which were inscribed the words of St. Paul: “God forbid that I should glory save in the Cross of our Lord Jesus Christ.”

St. Pius V said his daily Mass very early in the morning, preceded by an hour’s meditation and followed by at least an hour’s thanksgiving. He had a great love for the Blessed Mother. He promoted the recitation of the Holy Rosary and attached many indulgences to it, as well as to the recital of the Little Office of Our Lady. He was very devoted to his patron St. Michael the Archangel, and to St. Thomas Aquinas whom he proclaimed Doctor of the Church. (He also published all the works of he Angelic Doctor, in 18 volumes.)

Above all other devotions was his love for the Blessed Sacrament. So great was his reverence that he would never allow himself to be carried in the procession of Corpus Christi but always went on foot, bearing himself the monstrance with the Body of Our Lord. An English Protestant watching the procession was so impressed by the angelic and saintly aspect of the Pope that he became a Catholic shortly thereafter.

St. Pius V continued to practice his fasts and severe mortifications throughout his life. Till his death he slept on a hard straw mattress in his Dominican habit of coarse white serge, beneath which he always wore a hair-shirt. Over the course of his religious life he mastered his passions to such a degree that he seemed entirely free from them, more angelic in nature than human.

In Pius V we see a wonderful balance between charity and justice. He was severe towards heretics and public sinners but exceedingly merciful towards the repentant. He had the courage of his convictions, and never hesitated to call good good and evil evil. Consumed with the zeal for God and for the salvation of souls, he was fearless and uncompromising when it came to condemning and combating sin and evil. Cardinal Newman wrote: “I do not deny that St. Pius was stern and severe, as far as a heart burning within and melted with the fullness of Divine love could be so; but such energy was necessary for his times. He was emphatically called to be a soldier of Christ in a time of insurrection and rebellion, when, in a spiritual sense, martial law was proclaimed.”

St. Pius V expected much of others but even more of himself – he strove to be perfect as his Father in Heaven was perfect. Above all, he insisted on absolute truthfulness. A man who had once told him a lie lost his favor forever. Loving and prizing truth above all else, he had a horror of insincerity and flattery, and often sought adverse criticism of himself from his intimates. Nothing could make him change his mind once convinced of what had to be done. But he gave way on occasion to what he realized was another’s better judgment; nor did he shrink from simply beginning over again and making due rectification if by its results a course of action proved defective.

He forgave his enemies, and did good to them. It was said that his kindest acts were directed at those who had injured him. A nobleman who had threatened his life when he was Inquisitor was recognized by the Pope during an audience granted to a diplomatic mission. “I am the poor Dominican you once wanted to throw down a well,” he quietly said to him. “You see, my son, God protects the weak and innocent.” Then quickly putting an end to the man’s embarrassment, with one of his rare, enchanting smiles he embraced him and promised special consideration for his mission. A writer, condemned to death by the magistrates for having published slanders against the Pope, was brought before Pius V and not only pardoned but told that if in the future he had any fault to find with the Pope he should come and tell him personally.

Pius V, who always remained a simple monk at heart, used the rare moments when he could take a rest from the manifold responsibilities and anxieties of the office to retire to the Dominican monastery of Santa Sabina on the Aventine hill. There, in the silence and peace of the cloister, he would live again, sometimes for a few days, as a simple religious, regaining his spiritual and physical strength.

Back when Paul IV made Michael Ghislieri a Bishop, saying he had done so to “chain his feet and prevent his ever returning to live in monastic seclusion,” he replied that the Pope was “taking him from Purgatory to Hell.” After being himself elevated to the Pontificate, St. Pius told an ambassador that the trials and labors of the papacy were far greater causes of suffering than monastic discipline and poverty, or any other trial and hardship; and that the dignity of the Papal office could come near to being a hindrance to the soul’s salvation.

He had a horror of nepotism and would not allow any of his nearest relations to come to Rome unless charged with some special office, lest anyone should imagine that he was enriching them with the goods of the Church. And when they did come he was very severe. His very able and worthy nephew and fellow Dominican friar Michael Bonelli was made Cardinal but St. Pius forbade him to hold any benefice and required him to live a very simple and austere life. One of his other nephews, who had fought at Lepanto, later became involved in an scandal. The saint sent for him, lit a candle as he entered the room, and said: “You will leave Rome before this candle is burnt out!”

St. Pius’ holy severity and relentless opposition to evil-doers could not fail to produce enemies. The attempt of one of them to take the Pope’s life resulted in a famous miracle, confirmed by many witnesses. Pius V had a great devotion to the Passion of our Lord, and prayed for hours each night, with his crucifix in hand, devoutly kissing the Five Sacred Wounds. One night, as he knelt in his oratory, he was about to kiss the Feet of the Crucified, when, to his horror, the carved Feet were moved sharply aside. The Pope cried aloud, thinking in his humility that for some secret sin the Divine Savior refused his embrace. His servants thought otherwise, suspecting foul play. They wiped the Feet with bread and gave it to an animal which died after eating it. (The miraculous crucifix can be seen in the museum at the Santa Sabina monastery in Rome.)

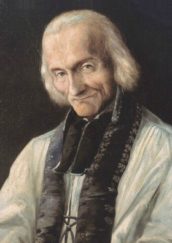

Death

St. Pius’ later life was one long martyrdom of pain. In January 1572 the malady (stones) from which he had suffered for many years increased to such an extent that he knew death was near. Even as the pain became unbearable he refused to be operated and have other people’s hands touch his body. A servant, seeing how weak he had grown in Lent from fasting, tried to get him to take a little more nourishment by secretly adding some meat sauce to his usual diet of wild chicory. The Pope detected it and reprimanded him thus: “My friend, do you wish me during the last few days of my life to break the rule of abstinence I have observed these fifty years?” His cook was forbidden, under pain of severest sanctions, to put any unlawful ingredients in his soup on days of fasting and abstinence, and during Lent.

After the Holy Week ceremonies, on Good Friday 1572, St. Pius V was obliged to take to his bed. Yet, ordering the crucifix to be carried into his room, he got up and prostrated himself several times before it in adoration. The rumor spread that the Pope was dying. Informed of the people’s great sorrow at his illness, he summoned up all remaining strength to give them the customary Easter Blessing for the last time. A vast crowd gathered in St. Peter’s Square; when the saint appeared on the balcony of the Basilica in his pontifical vestments and chanted the Blessing in a feeble but sweet voice, the silence was so intense his voice could be clearly heard even by those farthest off. The people wept, hoping and praying the Pope’s life would be prolonged.

This being the seventh year of his reign, he insisted on blessing the Agnus Dei, as was customary. (The Agnus Dei blessed by St. Pius V wrought many extraordinary and well attested miracles. Ferdinand II wrote to Pope Urban VIII that in a great fire which broke out in his chapel everything on the altar, including silver candlesticks, was destroyed, except an Agnus Dei of St. Pius V which was unharmed by the fire.)

Having regained a bit of strength the Pope determined to make his regular visit, on foot, to Rome’s seven Basilicas. To his physicians, household and Cardinals who tried to dissuade him for fear that he would die on the way, he replied “God Who began the work will see it to the end.” At the Lateran he wanted to climb the Holy Stairs but was unable to, and instead kissed the bottom step in tears. The crowds thronged about the saint as he gave them his last blessing. It was his final mingling with the Roman people who had learned to revere and love him so much. On the way back to the Vatican he spoke to a group of English Catholics exiled by Elizabeth. Before recommending them to the care of a Cardinal he exclaimed: “Lord, Thou knowest I have always been ready to shed my blood for their nation.”

Returning to the Vatican St. Pius took to bed from which he was not to rise again. In the last days he continuously made Acts of Faith, Hope and Charity, Thanksgiving, and Contrition. He had the Penitential Psalms and the Passion read aloud. Four days before death, no longer able to say Mass, he received Holy Communion offering himself as a holocaust to God.

On April 30 the Pope received Extreme Unction. He was clothed in his Dominican habit in which he wished to die. After receiving the Viaticum he spoke to the group of Cardinals who scarcely left his bedside, telling them that he had, from the first day of his Pontificate, vowed to spend himself utterly for the Church, and that he now recommended the Church to them. “Give me a successor,” he exclaimed, “full of zeal for the glory of God, who will seek the honor of the Church and the Apostolic See!” He stated that, although his sins and failings had not allowed him to see the final achievement of all he had endeavored to do, he adored God’s holy will and accepted His judgments. Among his final utterances were repeated incitations to continue the allied crusade against the Turks.

Henceforth, lying in agony, he only spoke to God, constantly kissing the Five Wounds of the Crucifix which was never out of his hands. Those nearest him made out the words, alternated with the prayers he was offering for his people: “Lord increase my pain, but may it please Thee also to increase my patience!” With this heroic act of love the perhaps greatest son of St. Dominic gave up his soul to God, at 5pm on May 1, 1572. He was 68 years old.

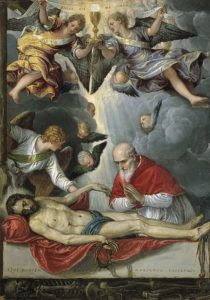

Upon opening his body the doctors found stones of such size they wondered in amazement how he had been able to live with the pain they must have caused him. After his death St. Pius’s body remained fresh, supple and fragrant as that of a child. It was laid out in St. Peter’s Basilica, which for four days could scarcely contain the crowds. Numerous miracles of healing were reported.

St. Pius V wished to be buried at Bosco, for he considered himself unworthy of being amongst so many holy Popes in Rome. But in 1588 Sixtus V had his relics translated to the tomb in Santa Maria Maggiore which he had prepared for his dear friend and benefactor.

Clement X beatified Pius V in 1672. The miracles chosen for the beatification were an instantaneous cure of a sick man by a fragment of the habit of the saint, and the miraculous preservation of two paintings of St. Pius V in a great fire which destroyed everything else in the palace of the Duke of Sezze. Clement XI canonized him in 1711. May 5 was appointed as his feast day.

All for the glory of God and salvation of souls

The incredible work this frail old monk accomplished in his short 6-year Pontificate is truly a sign that he was aided by God in a special manner. Guided by the decrees of the Council of Trent (and with the help of St. Charles Borromeo) he reformed Church discipline, stamping out the remnants of Renaissance worldliness and laxity. He issued the Roman Catechism, promulgated the Roman Missal and Breviary, and published the works of St. Thomas Aquinas. A zealous defender of the rights of God and the Holy Mother Church, he never allowed the power and prestige of any person to sway his determination to do what was right in the eyes of God – the most famous example being his excommunication of Queen Elizabeth I.

St. Pius V would be forever remembered as a glorious defender of Christendom, for it was his holy zeal and indomitable will in the face of a mountain of opposition from European sovereigns that broke the power of the Ottoman Empire and saved Europe from an Islamic conquest.

But above all he was a true father and pastor of souls, and like all good fathers was not afraid to use firm measures when necessary. Knowing that there was only one true path to salvation, St. Pius V was an uncompromising champion of doctrinal orthodoxy. He fought heresy tooth and nail and never gave an inch when anyone, no matter how powerful they might be, promoted erroneous teachings. In doing so, he was often as much of an annoyance to Catholic clerics and monarchs as he was to Protestant ones. Made utterly fearless by his great love of God and zeal for the salvation of souls, he succeeded in completely wiping out heresy in Italy.

Let us pray that the good God, in his infinite mercy, may have pity on us and send us – undeserving though we are of such a grace – a new St. Pius V. A Pope holy and fearless, full of ardent and heroic zeal for God, intransigent in his Faith and convictions, ready to rid the Church of the heretics, apostates and enemies of God who have taken over; to awaken Europe from her suicidal apathy and apostasy; and to restore all things in Christ.

Sancte Pie Quinte, ora pro nobis!

—

The Sword of Saint Michael: Saint Pius V (L. Browne-Olf) – pdf

The Life of St. Pius V (Fr. T. A. Dyson) – pdf, text, kindle format

Saint Pius V: Pope of the Holy Rosary (C. M. Antony) – pdf, text, kindle format

St. Pius V, the Father of Christendom – pdf